No one ever became a journalist to be loved, not even those guys with the perfect hair and ready smiles who were always destined to present the news (or the weather) on TV.

When you were going to have a career sticking it to The Man, that didn’t matter.

Being on the outer gave you an inner glow.

Sure, there were always those surveys that lumped journalists with used car salesmen on the trust scale. But we journalists knew the readers and viewers didn’t really think that way.

I mean, no offence, but a used car salesman wouldn’t know how to spell public good.

Besides, we didn’t really stop and think about it. We were too busy fighting the good fight to worry whether it was the right one for the readers and viewers. Of course you trust us. You’d miss us if we weren’t around. This much we knew.

Turns out we were wrong.

Over recent years, as our ranks have dwindled, I really believed there’d be an uptick in support for journalists and journalism. But, no, it turns out the media is more on the nose than ever before.

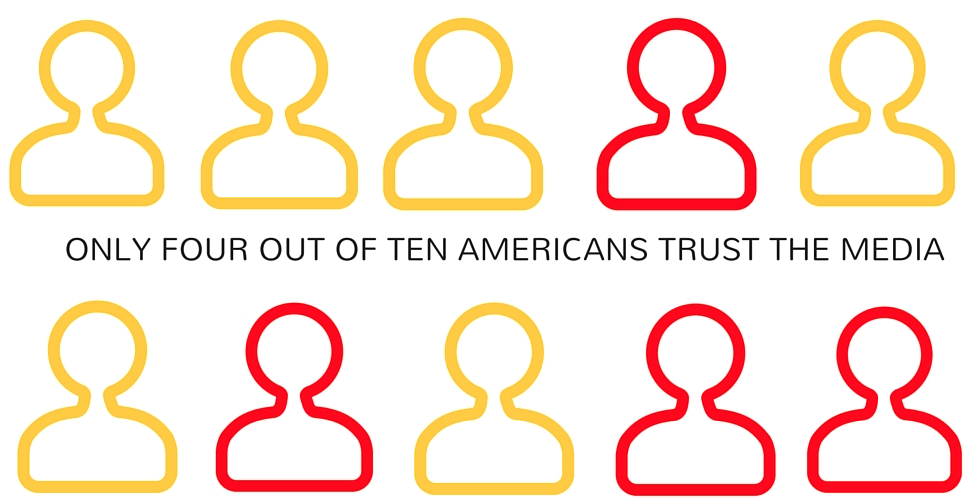

That’s what Gallup recently found. Its annual survey, released late last year, shows that only 4 out of 10 Americans trust the media’s ability to report the “news fully, accurately and fairly”.

That’s equal to the historic low, first hit in 2012 and again two years later, and 15 points down from the halcyon days of 1999. For more on the poll, here’s a link.

Worse still, trust is lowest among younger Americans. Only 36 per cent of those surveyed aged between 18–49 years old had faith in the media. Isn’t that the cohort we journalists need to keep reading, seeing and listening to our stuff? We may be in real trouble.

This isn’t an US-only trend — and it may well be far more profound than a bunch of Millennials saying they trust what their friends say on social media more than what they read in the New York Times.

The painful truth is that mass media is losing ground among the very people it was designed for: the mass.

Released at the Davos summit earlier this year, the annual trust barometer by Edelman, the global communication firm, uncovered a growing disparity — a trust gap — between the informed elite (15 per cent of the population) and the rest, the masses.

The averaged gap across four key institutions (media, business, government and NGOs) was widest in the US, at 20 per cent. This is the sore being so expertly picked at by Donald Trump.

But “following shortly behind are the UK, France, India, Australia and Mexico.”

(As a British-born Australian, I’m shocked: on par with those phone-tapping tabloid Poms!)

And, here’s Edelman’s most devastating conclusion: in our networked society, true influence lies in the hands of the mass rather than the elite.

(The elite have more faith in institutions; I guess they would tend to trust themselves.)

“The net result is a new phenomenon where the most influential segment of the population is at the same time least trusting,” concludes Edelman.

The truth is that a ‘person like yourself’ is now more trusted than a CEO, a government official or a journalist.

The flow-on: “Peer-influenced media — including search and social — now represents two of the top three most-used sources of news and information.”

Clearly, we journalists have for some time been writing about and listening to, the wrong people. We’ve been in the wrong relationship. The mob finds us less than trustworthy — and instead of doing something about it, we’ve been ignoring them for years. Or so it seems.

The question now is, what can be done? Is it all a bit late in the day?

Well, we can’t un-crack the egg, but we just might be able to learn how to make a better omelette. Here are three quick thoughts:

- Search for solutions. Later this month the Society for News Design and the Trust Project, started by journalist Richard Gingras and scholar Sally Lehman and funded by Craig Newmark, the founder of craigslist, will host a two-day event at City University New York (where I’m studying) that is aimed at finding ways to better signal trustworthiness in the news. It has a admirable ambition: to create ‘trust’ prototypes that can then be field-tested with audiences. I hope to go and will report back if I do. But there’s nothing stopping other organisations — media, NGOs and anyone else interested in the restoration and reform of the media — holding similar events to grapple with the same issue. Any takers in Australia?

- Celebrate what journalists can do. At CUNY my own project, Clevr, is dedicated to helping readers discover the sharpest analysis and commentary via the work of individual journalists across mastheads. For example, on the evening of Super Tuesday, I curated (and linked to) six journalists who were making sense of that night’s events. The idea is to give readers a rich, content experience — a deep-dive — on a subject in the one place. My pitch: we do the reading, you do the living. The journalists cited on Super Tuesday were published in the LA Times, the Washington Post, Fortune, ABC News (the US network), FiveThirtyEight and the New Hampshire Union Leader. The more we learn about what the audience wants, the smarter Clevr will get. This may or may not have legs (the question is, who’ll pay for it?) but something that celebrates journalists in the public space can’t be a bad thing, right?

- Let’s start teaching for the realities of this new world. The issues discussed in this post are a bit gloomy but they are fixable. We in the academy need to teach the next generation of journalists how to listen first and foremost and how to work in collaboration with the audience. There are signs that is happening. The hope then is that journalists will start creating the content their audiences actually want to read and share — rather than the stuff journalists think they should digest. Journalism has plenty of tools at its disposal to do just that (and new ones are coming out everyday) so what’s our excuse? That we still have all the answers?

When I went to a university J-school the first time, a thousand years ago, I assumed I’d leave with a great grounding and get a job. Sure, experience would fill me out, teach me how to actually work, but the point was, the readers would be — or should be — grateful to have me around. When I leave J-school this time, I will know that only a fool can afford to think that way. The challenge in front of me is to work out what to do about it.

This blog was first published on Medium on March 12 2016